The science behind our relationship with food.

It seems rather simple. You are having a bad day, and you decide to grant yourself some sugary indulgence. You stop by your favourite bakery or cafe, order a slice of chocolate cake, and stop thinking about everything else. For a brief moment, the world is about you and that slice of cake in front of you.

Replace the cake with something that you love, and you can certainly picture yourself in this situation. But it’s not just mood that governs what we put on our plates and in our mouths. “Of course not,” you say. “I make conscious choices about what I eat on a daily basis.” Well, there is a lot more to that story, and Cognitive Neuroscientist and Psychologist, Dr Rachel Herz helps us understand the many factors that influence our eating habits.

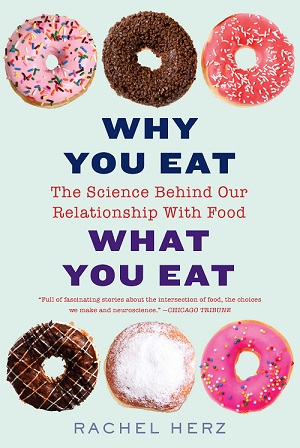

Herz’s book -“Why You Eat, What You Eat; The Science Behind Our Relationship With Food,” is part scientific and part psychological exploration of our food choices. An expert in the science and psychology behind the senses of smell and taste, Herz presents and summarizes numerous studies that show us how complex our eating patterns are. From what we read on the labels, to the shape, size and colour of our plates, to the sights and sounds that surround us- our relationship with food is a bit of a puzzle. The circumstances that lead us to indulge in that slice of cake is just one small piece in this large complex picture.

Over Skype, I chatted with Dr Herz about her book, food influences, grocery shopping, and finding a way to eat what we love, without going overboard. Here is an edited version of the conversation.

TYT: We live in a world where diets have become specific. But reading your book made me realize that there is no simple reason for why we eat, what we eat. Why did you decide to share the complexities of our food choices in this format for the general audience?

Rachel Herz: The simple answer is that I love food. A little bit more context is that my research background has been on the sense of smell for almost three decades. I have been involved in research about taste and flavour, and on motivated behaviour and cognition. I have a very strong background in probably the two senses people think of most when it comes to eating- smell and taste. So I really wanted to share that knowledge with people through this book. But to be honest, it was not that simple. This is my third popular science book. My first book was about the sense of smell, called the “The Scent of Desire“. My second book was about the emotion of disgust, and disgust is a taste-based emotion. Each book posed different challenges for me as a writer and scientist. My goal always has been to present information to the general public in an exciting and informative way. Writing this book was an interesting process. There were certain things I learned along the way that I did not know beforehand. Looking back, I am glad I took on this journey.

TYT: So why is it that certain foods make us feel so much better on bad days? Is it just the sugar rush?

Rachel Herz: Part of it is that. There are these neurochemicals that are released when we are eating highly palatable foods. Sugar releases dopamine, endorphins and also effects serotonin production- and these neurochemicals are involved in our wellbeing. High fat, high sugar and high salt are the foods that we turn to when we need comfort. These are all very pleasurable sensations. They also tend to be components of the foods that we ate as children during special occasions- when the family was coming together or we were being specially cared for or sometimes they were special treats. These foods become comforting because they are emotionally associated with the feeling of comfort. Our senses of smell and flavour are very much tied to emotion and memory. These flavours from childhood come together and recreate that feeling of a warm hug.

This also depends on the person’s upbringing. If they may not have had many of these special moments with food, then they are really just going for the neurochemical hits- the salt, sugar and fat. There is also a cultural element involved. Depending on where we are from, we crave certain tastes. Often these foods have high sugar and fat, but they don’t necessarily have to.

TYT: You point out a few things about our present food culture. You talk about the “ease, visibility, and access,” or opportunistic availability of food, Also about the media imagery and messaging of food that bombards us on a daily basis.

In this age of constant exposure to food- visual and otherwise, are we making the right choices?

Rachel Herz: A lot of the times, we are not making the right choices. We are programmed to be attracted to food, and the more food is presented to us, the more motivated we feel to consume it. We evolved in a landscape where food was scarce and finding food was the goal of the day, in order to survive. The present portrayal of food is highly appealing to us. We are triggering desire outside the context of appetite. On the other side of this spectrum are people who do not have access to good food. They live in food deserts. They are also exposed to calorie dense, often non-nutritious food that encourages them to eat more. This can lead to all kinds of problems from a health and weight perspective. This is a serious issue.

TYT: How can diet labels impact our food choices?

Rachel Herz: There is a paradoxical effect of seeing products with diet labels. When we choose products with such labels, we think that we have not consumed very many calories. We feel entitled to eat more later. Even when something is actually high calorie, and people are manipulated to believe it is low calorie, they will eat more later. The calorie content then becomes inconsequential compared to what we think about it. Interestingly this also has an impact on our metabolism. We think that we are consuming something that is negligible calorically, so our metabolism will actually stall.

The best way is to eat the real full product, and not the diet version of it. In doing so, you will feel more full. Low fat is often more sugar, which is also not good. Diet products and artificial sweeteners can change our metabolism and affect our microbiome population, which can, in turn, impact our digestive system.

TYT: You write not just about taste and food preferences, but also about purchase decisions. Something that stood out for me in this context was how bringing a bag influences grocery shopping. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Rachel Herz: The effects of bringing your own bag for grocery shopping work when you have the free will to do so, and you aren’t being penalized for not bringing one. When the effects of this act were studied, two important observations emerged. One, people purchased more organic products. That stems from the fact that these people are already environmentally conscientious and associate organic food with the same. The other thing is, and this a little bit amusing, when people carried their own bag, they also purchased more treats. It was observed that they put chips, cookies and ice creams on to the checkout belt when they brought their own bag in the free will scenario.

The thing is, we have this constant balancing act going on in our heads. We feel we should give ourselves a reward when we do something good. Since we are in the grocery store, we see all this food, and the reward ends up being something tasty. The study also found that this was only a factor when people were shopping for themselves. If the person was shopping for the family, then these effects don’t come into play because the shopping list is more specified and budget factors are considered.

This kind of underlying need to balance virtues and vices is also a major reason why most diets fail. Even if our intentions are not to buy or consume those treats, we feel the need to reward ourselves. These are some of the perils of our modern existence – having access to all the things we want to eat, all the time.

TYT: How can food writers contribute to a better food dialogue? What kind of food writing and imagery would you like to see out there?

Rachel Herz: The purpose of my book was to give people information so they are able to take control back with the food rather than feeling that the food was controlling them. When people have information about all the influences that go into their shopping experiences, they will feel empowered to both understand and take control of these impulses. Food writing should be along the lines of educating people and providing them with the right information.

Although, I do wonder if it’s better that we don’t know all of these influences. For example, if we tell people that when you shop online, you are less likely to buy treats, people may remember this fact and go looking for cookies and treats. I think it is essential to present information in the right way, so people don’t run afoul of their own behaviours.

Realistic representation of food is also important from a visual point of view. When people see cooking shows and food, it is not that they run into the kitchen to eat the exact same food. They just become motivated to eat. When they see real people cooking real food, and all the work and mess that goes into it, the reaction may not be so immediate.

TYT: In her book, Butter; A Rich History, Elaine Khosrova writes, “Indeed, one of the best lessons learned from my career in food and cooking is that gratification is something of a paradox: Too much of a good thing often diminishes the pleasure we derive from it.”

At present we have this love-hate relationship with specific foods and ingredients, What is your take on this kind of relationship?

Rachel Herz: That is absolutely true. I think too much of a good thing is not that great. We have to be conscious of the experience of eating. I don’t like the overuse of the word mindfulness and the way it has been brought into the western world, but I do think it is important to be mindful. We need to be in the moment, engaged with what we eat so that we can perceive the pleasure and also recognize when it starts to diminish. Our senses become satiated before our stomach. This may sound a bit too much, but at least thinking about it a few times while you are consuming something will help develop that sense. This is also my biggest personal takeaway from working on this book.

Rachel Herz’s tips for better eating:

–> Eat real food: Avoid processed food and diet labels. Eat the full-fat product, so you know when you are full and you stop. It is okay to sip that diet soda occasionally. The problem is overconsumption.

–> Moderation and variation: Eat what you want in moderation and vary what you are eating. If you are just eating kale and tofu, that’s not healthy in itself because you are not getting enough variation and macronutrients. You want to get your nutrients from a wide variety of sources.

–> The pleasure principle balance: The first bit of chocolate cake is amazing. You take that bite and savour it. The third bite, also still really good, but not as great as the first. But when you get to the fifth or sixth bite, maybe it’s not so good anymore. Further from that, you realize that you are not really getting the pleasure you sensed when you first started eating. That’s when it is time to put the fork down.

For more information visit: https://www.rachelherz.com/

Featured Image Courtesy: Pexels.com

You May Also Like:

Sweet As Sin; The Unwrapped Story Of How Candy Became America’s Favorite Pleasure